I am afraid “Evangelicals” have come to expect something when they read systematic theology, and that is that there will be a nice and neat presentation of pre-digested, pre-codified truths and theorems about God and such. Indeed we should expect a certain ordering and systematizing of such things when we read “systematic theology;” but what is often forgotten is how our beliefs today came to be in the first place. The early Christians (“The Patristics” or “Church Fathers”)  were presented with a whole host of issues to try and hash out; primarily trying to articulate the nature of God and Christ. Some of the ideas that were held then, early on, would later and now be considered heresy; but that is what happens sometimes when we try and speak about an ineffable God who is worthy of worship. I juxtapose these two poles of theology (the “finished product” — systematic theology and the “hashing out process” — constructive theology) to remind us that theology is most certainly a “relational endeavor” (and this only flows from the reality that God is a relational/trinitarian God); this being the case, just when we think we’re finished (systematic theology) we are turned back upon our own inadequacies to actually capture God in all His grandeur, we are turned back to the hashing out process (constructive theology) to try and “fine-tune” (if possible) our thoughts about our God. Here is what J. N. D. Kelly says about such things (in the context of speaking about the “Church Father’s” approach):

were presented with a whole host of issues to try and hash out; primarily trying to articulate the nature of God and Christ. Some of the ideas that were held then, early on, would later and now be considered heresy; but that is what happens sometimes when we try and speak about an ineffable God who is worthy of worship. I juxtapose these two poles of theology (the “finished product” — systematic theology and the “hashing out process” — constructive theology) to remind us that theology is most certainly a “relational endeavor” (and this only flows from the reality that God is a relational/trinitarian God); this being the case, just when we think we’re finished (systematic theology) we are turned back upon our own inadequacies to actually capture God in all His grandeur, we are turned back to the hashing out process (constructive theology) to try and “fine-tune” (if possible) our thoughts about our God. Here is what J. N. D. Kelly says about such things (in the context of speaking about the “Church Father’s” approach):

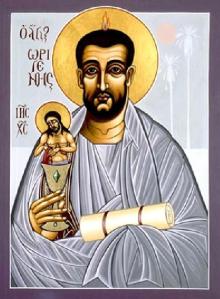

If he is to feel at home in the patristic age, the student needs to be equipped with at least an outline knowledge of Church history and patrology. Here there is only space to draw his attention to one or two of its more striking features. In the first place, he must not expect to find it characterized by that doctrinal homogeneity which he may have come across at other epochs. Being still at the formative stage, the theology of the early centuries exhibits the extremes of immaturity and sophistication. There is an extraordinary contrast, for example, between the versions of the Church’s teaching given by the second-century Apostolic Fathers and by an accomplished fifth-century theologian like Cyril of Alexandria. Further, conditions were favourable to the coexistence of a wide variety of opinions even on issues of prime importance. Modern students are sometimes surprised at the diversity of treatment accorded by even the later fathers to such a mystery as the Atonement; and it is a commonplace that certain fathers (Origen is the classic example) who were later adjudged heretics counted for orthodox in their lifetimes. The explanation is not that the early Church was indifferent to the distinction between orthodoxy and heresy. Rather it is that, while from the beginning the broad outline of revealed truth was respected as a sacrosanct inheritance from the apostles, its theological explication was to a large extent left unfettered. Only gradually, and even then in regard to comparatively few doctrines which became subjects of debate, did the tendency to insist upon precise definition and rigid uniformity assert itself. (J. N. D. Kelly, “Early Christian Doctrines,” 3-4)

This illustrates my points above, and in fact pulls them back in a bit as well. Theology is a relational “learning” enterprise, it is man’s attempt to “speak with God” about God in Christ through the illuminating Holy Spirit. Sometimes if we are going to do this we must run the risk of heresy, isn’t worshipping in “spirit and truth” worth this risk? Furthermore, I said Kelly “pulled” some of what I said above “back” a bit because at first blush some of what I was communicating previously may have sounded like I was saying that we need to “re-hash” all that has gone before us (so that we end up with something completely new); but this really wasn’t what I was intending to say, instead it is what Kelly has said. That we need to recognize the “solid gains” made by “our fathers,” and then build and work out the implications of what “our spiritual parents” have said before — sometimes this ends in discarding certain ancient trajectories, and other times it means we discover great seeds of truth that only now begin to blossom as we continue to water the seedlings of our rich heritage (make sense?).

Are you willing to be a heretic?